Welcome to a new series exploring the early classics of science fiction and fantasy, with your host, Mr. Dusty Jackets, OM OB FEC Bsc(Cantab) MChem(Oxon)MscD CMAS CM CWP FWS NBCCH PLS

Dear Reader,

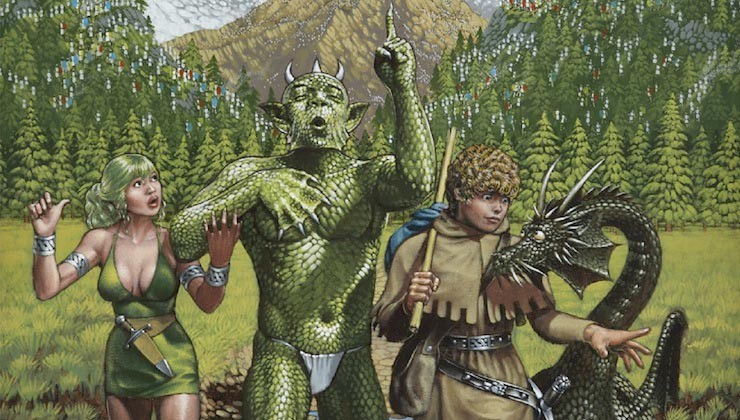

I was pottering around in my library the other day, top-shelf to the right of the mantle and to the left of my collection of Glaucopsyche lygdamus palosverdesensis, when my eye fell on the twelve narrow volumes of Robert Asprin’s Myth Adventures. On a whim I took out the first book in the series, Another Fine Myth, and pondered its striking cover: a young Skeeve, his pet dragon Gleep, the demon Aahz, and the green-haired Tananda striding towards me. I was suddenly transported back to my childhood and the beginnings of my journey into the world of science fiction and fantasy.

Although memory gets a bit faded after so many years, Another Fine Myth may have been the very first fantasy novel I selected for myself, without prior recommendation, and I assure you that it wasn’t merely the cover that drew my interest. It was actually the author, Robert Asprin’s, name on the spine that made me first pick it up, and perhaps the cover (and wondering at how such an odd group could ever be brought together) that got me to buy it.

To understand why a boy suffering the miseries of early teen-hood would have interest in an author that had, to that point, written a single novel (Cold Cash War)—which, by the way, I had not heard of at the time and have never had an opportunity to read since—it is important to explain what was happening to the world of fantasy in the late ’70s. One year before the publication of Another Fine Myth, a small company, Tactical Studies Research, Inc., (TSR) introduced a game called Dungeons & Dragons to an unsuspecting public, and my older brother and I were among the first group of players to adopt it as a principal hobby.[*]

The game was a revelation, and became even more of one in 1978 when Gygax and TSR released the Player’s Handbook for an advanced version of the game (Advanced Dungeons & Dragons or AD&D), which, by the way, has one of the best covers of all time.[†] D&D and AD&D were entirely different from every other game (board or strategy) that we had ever played. They invited players to create worlds and characters of their own design. You could replay the plot of The Hobbit, or Frodo’s journey to Mount Doom. You could recreate Oz, or build castles in the clouds. Anything was possible, the only limitation being your own imagination (that might have been the game’s tag line, actually). The point is, we were hooked. We spent countless hours drawing detailed maps of imaginary kingdoms on graph paper and riding our bikes from hobby store to hobby store looking for new supplements or copies of Dragon Magazine, or (during the great dice shortage of 1979) just looking for dice.[‡] At the hobby shops we were introduced to an odd variety of characters: newly-minted roleplayers, gray-beard wargamers, and now and then the odd member of the Society for Creative Anachronism (SCA).

If you have never heard of the SCA you can think of its members as people that have taken roleplaying to the next level. They have removed it from the virtual world of paper and pencil, and transported it into real life. They make their own clothes and armor and weapons, they join kingdoms and go to gatherings where they attempt to recreate all the best parts of the Middle Ages (damsels and knights and royalty), but not the bad parts (plague, pestilence, witch burnings, and so on). For me and many of my friends stuck in suburban Houston and unable to even conceive of how to get involved in such a grand undertaking, the tales of these gatherings and the characters that inhabited them were the stuff of legend.

In a very roundabout way, this takes us back to Another Fine Myth and my interest in Robert Asprin. He was an early member of the SCA—but more than being “just a member,” as Yang the Nauseating, Robert Asprin was a founding member of the legendary SCA kingdom the Great Dark Horde, which infamously “walked out of the trees” at a SCA gathering in 1971. The Great Dark Horde was everything I aspired to be: irreverent and devoted to freedom, camaraderie, and friendship. And here was a book written by Yang himself!

Nor was I disappointed. Another Fine Myth was everything one would expect from a man who, in his spare time, would don a cheap sheepskin vest and run around as the Mongol Khakhan, Yang the Nauseating. It, and the other books in the series, are filled cover to cover with humor. From the wry quotes (some real and others fabricated) heading each chapter:

“One of the joys of travel is visiting new towns and meeting new people.” –Ghengis Khan

To the witty banter of the characters:

“Pleased ta meetcha, kid. I’m Aahz.”

“Oz?”

“No relation.”

To the world itself (for those who have read it I will only mention the Bazaar at Deva as perhaps one of the coolest places created in fantasy history), each page reveals a new joy.

As for the stories, the form of each book is rather simple: the characters stumble upon or are thrust into a quest (that usually seems impossible), and we (the readers) follow along in the hilariously destructive wake of their adventures. In a Myth Adventures book the plot isn’t really the point; instead the real joy is in experiencing how Asprin reveals, revels in, and ridicules the fantasy genre, all without being mean. Take the first volume of the series, Another Fine Myth: the book begins with—and indeed the entire premise of the Myth Adventures is based on—a series of practical jokes gone wrong.

Skeeve is an apprentice, and a rather woeful one, of the great magician Garkin. To teach Skeeve a lesson about not taking his magical training seriously, Garkin summons a terrible demon. The demon turns out to be Aahz, a green-scaled being from the land of Perv (that does not make him a Pervert; to be clear, he is a Pervect) who is not so much a demon as a magician friend of Garkin’s. It turns out that magicians across the dimensions have reciprocal agreements to summon their fellow practioners to scare their apprentices straight.

I’ll let Aahz explain.

“I thought you said you were a demon?”

“That’s right. I’m from another dimension. A dimension traveler, or demon for short. Get it?”

“What’s a dimension?”

The demon scowled.

“Are you sure you’re Garkin’s apprentice? I mean, he hasn’t told you anything at all about dimensions?”

“No.” I answered. “I mean, yes, I’m his apprentice, but he never said anything about demon-suns.”

“That’s dimensions,” he corrected. “Well, a dimension is another world, actually one of several worlds, existing simultaneously with this one, but on different planes. Follow me?”

“No,” I admitted.

“Well, just accept that I’m from another world. Now, in that world, I’m a magician just like Garkin. We had an exchange program going where we could summon each other across the barrier to impress out respective apprentices.”

Unfortunately, during the “demon-stration” (see what I did there) Garkin is killed by an assassin. It is further revealed that, as an added joke, Garkin somehow made it so Aahz could not longer use magic. To try and get his powers back and track down the man that sent the assassins to kill his friend, Aahz takes Skeeve on as his apprentice. Thus begins the long (many volume) partnership of Aahz and Skeeve. Eventually they will add to their team a baby dragon (Gleep) that has a one-word vocabulary (“Gleep!”), the nymph assassin (Tananda), Tananda’s erudite brother (Chumley the Troll), and several former members of the interdimensional Mafia, among others.

But leaving aside the jokes and the colorful supporting cast, the real strength of the books, what lends them warmth, and what makes them more than merely a collection of punchlines, is the relationship between Aahz and Skeeve. Through all the dimensions, from the scorching deserts of Sear to dark and damp Molder, it is the dynamic between the outwardly gruff, ever-capable, but morally ambiguous Aahz, and the seemingly bumbling and yet surprisingly effective and always morally centered Skeeve, that gives the Myth Adventures its heart. And their banter! In this author’s opinion, the give-and-take between the two ranks them among the best comedy duos of all time.

“Well, kid,” Aahz said, sweeping me with an appraising stare, “it looks like we’re stuck with each other. The setup isn’t ideal, but it’s what we’ve got. Time to bite the bullet and play with the cards we’re dealt. You do know what cards are, don’t you?”

“Of course,” I said, slightly wounded.

“Good.”

“What’s a bullet?”

So, if you like your writing brisk, your action packed and your wit quick, the Myth Adventures series is just what you’re looking for. And, if the books lose a little punch in the later volumes or you find you don’t like the writing, you can always do what my thirteen-year-old self did back in the day and spend your time trying to get the references (and jokes) Asprin makes in those legendary epigraphs that head each of his chapters.

They are historic:

“In times of crisis, it is of utmost importance not to lose one’s head.” –M. Antoinette

And literary:

“To function efficiently, any group of people or employees must have faith in their leader.” –Capt. Bligh (ret.)

They span all time, from long ago:

“Anyone who uses the phrase ‘easy as taking candy from a baby’ has never tried taking candy from a baby.” –R. Hood

To long long ago, and in a galaxy far far away:

“One must deal openly and fairly with one’s forces if maximum effectiveness is to be achieved.” –D. Vader

And, of course, you can always find one that is appropriate for all occasions:

“All’s well that ends well.” –E.A. Poe

Which is true even for rather rambling book reviews.

Your most obedient servant,

–Dusty Jackets

[*] To those of you who are sticklers for accuracy in these things, I am aware that the first edition of D&D (or OD&D), the Gary Gygax and Dave Ameson version, was actually published in 1974, but that game was relatively niche, and was also very different from the version of the game that really introduced roleplaying to the masses in 1977.

[†] I spent countless hours studying the Player’s Handbook cover wondering at the horrors that would befall those characters once the thieves removed the ruby eye from the statue.

[‡] Several 1979 editions of the D&D box set didn’t include the six plastic polyhedrons that made the game what it is, but instead included numbered paper chits and a coupon for a set of dice when they became available.

Dusty Jackets is one of a number of alter-egos of Jack Heckel, author of The Charming Tales, including the first volume: A Fairytale Ending (available in ebook and paperback), and The Pitchfork of Destiny, which has just been released as an ebook and will be released as a paperback on May 17th. If you would like to learn more about Jack Heckel or Dusty Jackets, visit Jack’s website.